The 1992 Olympic men’s basketball team’s legacy is vast. The ripple effects are still felt in basketball today. But all of the talk about the inspiring future hoopers across the world overlooks another way the team changed lives for the better. ‘s presence on the team was downright rebellious given his perception after his from the NBA.

Testing positive for HIV at that time drew a lot of derision from hateful people who treated those afflicted with the virus like filthy sinners who deserved their agony. Thankfully, attitudes have shifted forward since those times as the condition is more understood.

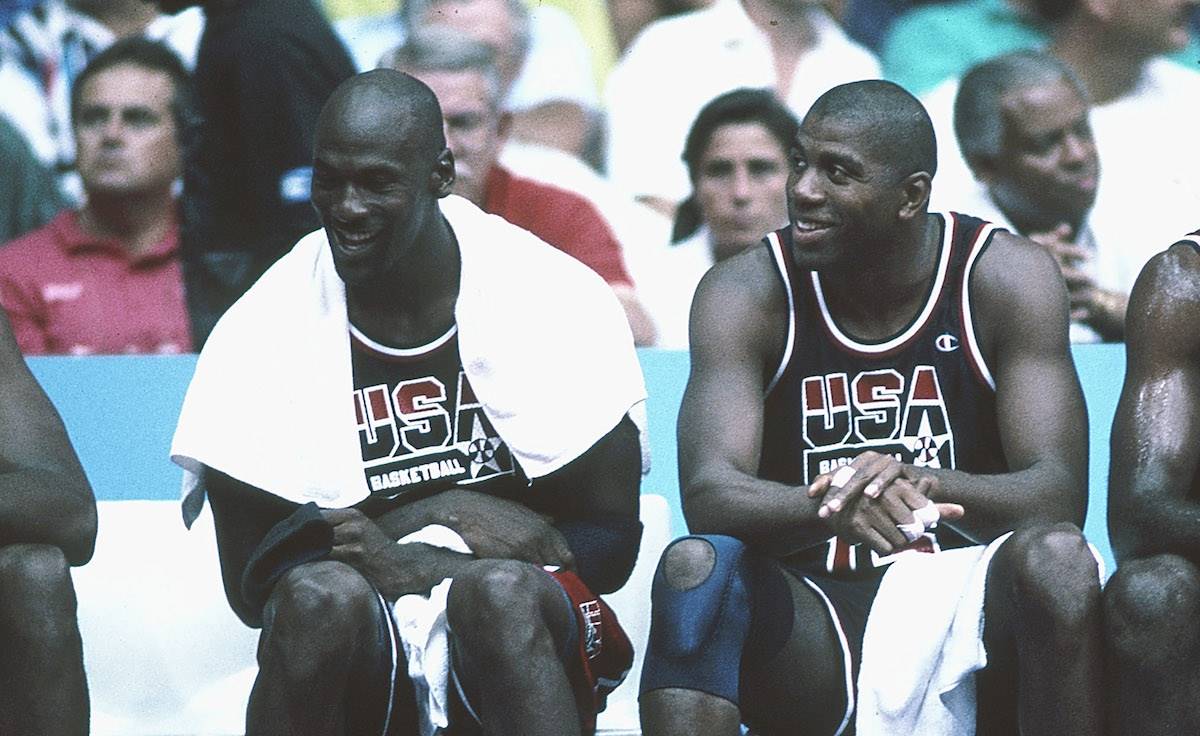

Decades before the phrase “player empowerment” entered anyone’s lexicon, the idea that the biggest and best players of the NBA’s first golden era would be on the same team in any capacity was stunning. Sure, back problems were severe at that point, and Christian Laettner was there for some reason, but the untouchable totality of their greatness — 17 All-Star appearances and 23 titles over the course of their NBA careers — was an once-in-a-generation event.

Even the teams they decimated en route to the gold medal were honored for the opportunity to be whomped by their idols.

“We felt like we were the luckiest guys in the world. We were going to play against the best,” Herlander Coimbra from Team Angola told in a 20th anniversary retrospective on the team. “But those guys were on another level — a galaxy far, far away.”

It wasn’t just special because of the spectacle that came with seeing Michael Jordan and play on the same team instead of against each other. It was also rare to see these players play nice for a change. The idea that all of these could also be friends when the game was over was unknown at the time.

The clip of Jordan, Bird, and Magic joking about MJ’s reputation with the refs during a photoshoot would’ve blown minds had it been publicized at the time.

In it, Johnson joked, “You can’t get too close to Michael, or it’s a foul,” which prompted Jordan and Bird to crack up laughing.

The for the Dream Team has been debated for decades, but Magic’s place on the team was noteworthy because of his circumstances.

Johnson retired from the NBA just a year before the Olympics after testing positive for HIV. The revelation was a groundbreaking moment for American culture, not just the NBA.

The HIV/AIDS crisis of the ’80s was a nationwide story, but ignorance about how the virus worked remained prevalent. It was painted as a “gay plague” by some in the media and the Reagan administration did little to help the first wave of victims.

It was a commonly held belief that the only people in danger of contracting the disease were gay, bisexual, or drug addicts — demographics of people that America has struggled to recognize the humanity in for centuries. Someone with Magic’s fame, success and openness about how he contracted the virus made millions realize that HIV could affect anyone. (Although that didn’t stop

from spreading after Johnson’s admission.)

Johnson returned to the court for the , but his appearance was complicated by the fact that some players felt uneasy being in the vicinity of Johnson, let alone play defense on him. Nevertheless, he played and ended the game with the MVP award and a shower of hugs as he left the court. Seeing most of the league’s main stars publicly support Johnson was deeply moving, and it probably helped get him on the Dream Team in the first place.

Unfortunately, this story doesn’t have a fairytale ending. After the Olympics, Johnson attempted to return to the NBA full-time, but

over his condition convinced him to leave the game for good.

Related

If you asked most people in 1991 if Johnson would still be alive 30 years after his diagnosis, most of them would likely say no.

Testing positive for HIV was seen as a death sentence at the time, but Johnson’s daily existence continues to show that living with HIV is possible with the help of and advancements in medical science.

Because HIV was still a novel virus when Magic contracted it, his treatments were seen as experimental at the time.

Their success with keeping him alive has helped to save thousands of people over the years. Education around how to avoid catching HIV in the first place has progressed as well. According to , the number of new HIV infections declined 8 percent from 2015 to 2019.

Johnson credits his place on the Dream Team for when his future seemed so bleak.